Fruit Insect News from Doug Pfeiffer (Fruit Entomologist at Virginia Tech - Blacksburg)

Wednesday, February 12, 2025

2025 Fruit Pest Management Recommendations Posted

This year's revisions to our fruit pest management guides are now available.

The guides are available for free in PDF form. Hard copies may be purchased.

2025 Spray Bulletin for Commercial Tree Fruit Growers Click here for PDF.

2025 Pest Management Guides

2025 Commercial Horticultural and Forest Crops (including Commercial Small Fruit, Commercial Vineyards, Commercial Hops) Click here for pdf.

2025 Home Grounds and Animals (including HomeFruit). Click here for pdf.

2024 Field Crops Click here for pdf.

More later,

Doug

Tuesday, February 6, 2024

2024 Fruit Pest Management Recommendations Posterd

This year's revisions to our fruit pest management guides are now available.

The guides are available for free in PDF form. Hard copies may be purchased.

2024 Spray Bulletin for Commercial Tree Fruit Growers Click here for PDF.

2024 Pest Management Guides

2024 Commercial Horticultural and Forest Crops (including Commercial Small Fruit, Commercial Vineyards, Commercial Hops) Click here for pdf.

2024 Home Grounds and Animals (including HomeFruit). Click here for pdf.

2024 Field Crops Click here for pdf.

More later,

Doug

Sunday, July 23, 2023

Appearance of Spotted Lanternfly Adults

This week, spotted lanternfly (SLF) adults began their appearance. There was an appearance of an adult in a vineyard in Bedford County on July 19. There is a possible appearance a day or so earlier that is being follow up on.

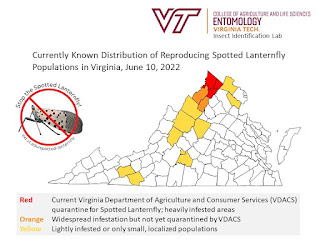

This map includes the most recent updates in geographic spread of SLF in Virginia, generated in the Insect Identification Lab in the Department of Entomology. Red counties are included in the VDACS quarantine; counties in orange have established populations but are not yet in quarantine.

The adult stage poses the greatest risk of immigration into vineyards, because of its mobility and attraction to grapevines. If adults are just showing up in an area, there is no need to overreact. In areas where SLF has been present in an area for a season or two, the pest pressure is likely to be higher. In the coming weeks, play close attention, looking for adults on cordons and canes. A provisional action threshold in vineyards is 5-10 adults per vine. I emphasize the term provisional. This may go up or down as we gain further experience with this insect in our vineyards. There is often a strong edge effect with this insect, and border sprays may be able to handle the problem, without spraying the whole block.

The Pest Management Guide chapters for Commercial Vineyards, Small Fruits and Hops can be found at this link (https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/456/456-017/456-017.html). There are several materials listed for this time of the season, when adults are the target. Once sprays start, reassess frequently. Pay close attention to the maximum applications or amounts applied per season, and watch preharvest intervals. I would very much like to hear more about this as it unfolds at your sites.

Here is a link to my SLF page (https://www.virginiafruit.ento.vt.edu/SLF.html). There is a table linked there listing SLF materials, with PHI and seasonal max levels. There are fact sheets post for SLF for general information, management in vineyards and in residential areas.

Let me know if you would like to discuss SLF at your location.

More later,

Doug

Tuesday, March 7, 2023

2023 Revisions to Fruit Pest Management Recommendations

2023 Commercial Horticultural and Forest Crops (including Commercial Small Fruit, Commercial Vineyards, Commercial Hops)

2023 Home Grounds and Animals (including Home Fruit)

2023 Field Crops

2023 Spray Bulletin for Commercial Tree Fruit Growers.

Watch for more later!

Doug

Tuesday, February 7, 2023

Update on Spotted Lanternfly

There will be further updates as this pest increases its presence in Virginia. More later, Doug P.

Thursday, July 28, 2022

Resources to Help in SLF Quarantine Compliance and Management

Spotted lanternfly (SLF) is a potentially devastating pest of grape, now expanding its spread in Virginia. In July 2022, VDACS expanded a quarantine zone from 3 counties to 12, including contained independent cities.

Many vineyards and wineries will now need to deal with the quarantine protocol. At least one person per company will need to get certified through a short, on-line training session ($6.00). That person may train others in the company to assure compliance. All shipments and vehicles leaving the quarantine zone will need to be inspected. Information on the quarantine protocol may be found here (https://www.vdacs.virginia.gov/plant-industry-services-spotted-lanternfly.shtml). This site contains the protocol as well as the current version of the quarantine map.

The training required for certification is easy and inexpensive. Access to the training may be found here (https://register.ext.vt.edu/search/publicCourseSearchDetails.do;jsessionid=E3FEE1B1C1921BA6848B382063FC0BDE?method=load&courseId=1066947).

When doing inspections for quarantine compliance, it will be necessary to know what life stages of SLF can be expected. We have graph posted online that conveys this information clearly (https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/ENTO/Ento-268/ENTO-268.html). This can be posted where appropriate in your operation.

Theresa Dellinger and Eric Day in the Department of Entomology have created a useful aid for the public on the SLF quarantine, entitled "What Virginians Need to Know About SLF Quarantine expansion" (https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/ENTO/ENTO-319/ENTO-319.html).

Beyond matters of quarantine compliance, we have online resources for SLF management. There is a fact sheet on SLF management, available in English and Spanish, available here (https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/ENTO/ENTO-323/ENTO-323.html). In a similar fashion, a fact sheet for SLF management in residential areas (https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/ENTO/ENTO-322/ENTO-322.html).

Needless to say, SLF is covered in our annual chemical control recommendations for vineyards and home fruit. The risk to tree fruits is not considered to be as great; SLF will be included here as needed. It should be noted that orchardists will still need to deal with quarantine issues.

VCE Pest Management Guide for Commercial Vineyards (https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/pubs_ext_vt_edu/en/456/456-017/456-017.html)

VCE Pest Management Guide for Home Fruit (https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/456/456-018/456-018.htmls.html)

Last but not least, I maintain a spotted lanternfly page in the Virginia Fruit Site ( https://www.virginiafruit.ento.vt.edu/SLF.html). I intend for this to be one-stop shopping for matters on SLF, and all the above links are active there.

I hope this is useful. More later, Doug

Wednesday, July 6, 2022

Spotted lanternfly update: Large expansion of quarantine zone

In May 2019, the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS) announced the establishment of a quarantine zone for spotted lanternfly (SLF). I posted on this here on 28 May of that year, and again on 3 June, when a public open house was announced to discuss compliance with the program. The quarantine zone initially contained Frederick, Clarke and Warren Counties plus the City of Winchester. A significant expansion of the zone is now planned, and will be formally announced in the next week or so. The quarantine zone additions will include the counties of Albemarle, Augusta, Carroll, Page, Prince William, Rockingham, Rockbridge, Shenandoah and Wythe, plus the cities of Buena Vista, Charlottesville, Harrisonburg, Lexington, Lynchburg, Manassas, Manassas Park, Staunton and Waynesboro. Here is the new zone map:

Here is a link to more information on the quarantine (https://www.vdacs.virginia.gov/pdf/spotted-lanternfly-quarantine.pdf). There will be public informational sessions to discuss the program, and facilitate compliance. One such meeting will be held on Aug 1, 5:50-8:30 PM, at King Family Vineyards. For more information, contact Grace Monger, gimonger@vt.edu (free with pre-registration, $10 at the gate). I will announce other sessions as I learn of dates.

One of the conditions of the quarantine is that at least one person within each company (vineyard, winery, orchard, hops yard, etc.) be certified to inspect and approve vehicles or shipments leaving the quarantine zone. The current certification program is linked here. Cost for a certification is $6.00.

The quarantine zone is being expanded because SLF continues to spread in Virginia. Different maps are prepared reflecting this spread. There are understandable differences in details among maps depending on the nature of programs - approvals that are needed for a quarantine, official identification of SLF samples, etc. Here are two current maps. The first has been developed within the Department of Entomology at Virginia Tech, by Eric Day and Theresa Dellinger. The second is maintained in a SLF site by the New York State IPM program at Cornell University.

These two maps reflect two infested counties not yet included in the quarantine: Campbell and Loudoun. An important point of the Cornell map is that it includes the whole range of SLF. A significant point here is that SLF has turned up in North Carolina, the first infestation for this state, in Forsythe County, Close to I-44. More information on the NC infestation can be seen here.

Summary: Important take-away points here are that SLF has continued its spread, now including the whole Shenandoah Valley, further incursions in the Piedmont of Virginia, and a significant jump into southern Virginia, almost certainly assisted by human transportation, at the junction of two major highways. There has been an expansion into North Carolina, close to (though not adjacent) to Carroll and Wythe Counties. VDACS is set to announce a significant expansion of the SLF quarantine zone in Virginia. Watch for annoucements of informational meetings in affected counties.

You can contact me for information on spotted lanternfly biology or management. For questions on the quarantine program itself, contact VDACS at spottedlanternfly@vdacs.virginia.gov, or 804-786-3515.

More later, Doug

Friday, July 9, 2021

Update on spotted lanternfly - first adults

Hello, everyone,

We are at crucial stage of development for our population of spotted lanternfly, both in terms of range expansion and seasonal phenology. You may remember that at the end of last season, we had detected SLF at a commercial vineyard for the first time, in a vineyard north of Winchester (we had earlier detected it on a table grape planting in Winchester). This week we found fourth instar nymphs at two commercial vineyards southwest of Winchester. Dr. Johanna Elsensohn, a post doctoral researcher with USDA-ARS, found a single nymph on a vine. At both of these Frederick County vineyards we found nymphs on tree of heaven on both sides of the blocks – the vineyards are essentially surrounded!

Fig. 1-2. Spotted lanternfly fourth instar nymphs on tree of heaven surrounding a vineyard.

Yesterday, the first adults of SLF for this season were reported. This is an important time of the season, since the adult stage is the main dispersal stage. From now until fall, there will be a time of movement into vineyard blocks if SLF is established in the area. Growers in such areas should be watchful. Adults will form large feeding aggregations, and can impost a large drain on the vine.

Fig. 3-4. Spotted lanternfly fourth instar nymphs on tree of heaven surrounding a vineyard.

In both of these vineyards, there were stands of young tree of heaven that had grown from cut trees. It will be helpful to remove tree of heaven, but it is important to not simply cut the trees with out supplemental herbicide treatment, because of the way these trees regenerate. Figs. 2 and 3 show nymphs on such small trees (Figs. 1 and 4 contain nymphs on mature trees). We are fortunate in having only a single generation of SLF. If we start the season with a low population of young nymphs, it is unlikely that significant immigration will occur, and additional sprays may not be needed. This can change with the mobility of winged adults.

Fig. 5. Adult spotted lanternfly

This year is likely to be a year of additional commercial vineyards with populations of SLF. Apple and peach orchards may also see feeding aggregations, but these may be transient. Hops are also fed upon, but more information is needed on duration and severity, Please let me know of observations at your plantings.

More later,

Doug

Wednesday, June 30, 2021

Cicada aftermath, and bird/cicada controversy

This year's emergence: This emergence of Brood X periodical cicada has now pretty much run its course – the adult stage anyway. If you have young fruit trees, it might be helpful to prune off damaged branches – this would prevent the nymphs from establishing on roots, helpful in the first formative years of the tree. Eggs normally hatch 6-10 weeks after oviposition. For us in Virginia, this was mainly a northern Virginia issue. Brood X extends up through eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey (remember this when you get to the hot topic note toward the end!) There were also populations of Brood X south of Virginia (parts of North Carolina, Tennessee and Georgia). Here are the maps for Broods IX and X: Fig. 1. Maps of periodical cicada Broods IX and X, from Marlatt (1907)

The broods were characterized and named by the USDA entomologist Charles Marlatt in 1907 (Marlatt 1907). But while Marlatt made a great formal study of these insects and determined the geographical broods, he was not the first to determine the 17-year cycle. A free African-American naturalist, Benjamin Banneker, living in Maryland, born in 1731, reported this after an 1800 emergence (Barber and Nkwanta 2014). He successfully predicted subsequent emergences. Both of these individuals played other important roles – Banneker helped survey the borders of Washington DC, and Marlatt led the creation of the first regulations designed to protect us from invasive pests).

There are three Magicicada species that make up each brood of periodical cicada. The local species composition can very a lot, even within a county. Last week we sampled cicadas in Frederick County: at Fort Collier in Winchester, 94% were composed of M. cassini (34:2), while at Star Tannery in the southwestern part of the county, 76% were M. septendecim (16:5). M. cassini are smaller, with the underside of the abdomen completely black, compared with the larger M. septendecim, with red on each sclerite.

Fig. 2. Side-by-side comparison of Magicicada septendecim (top) and M. cassini (bottom).

While M. cassini may lay their eggs in smaller branches, I’ve seen no comparison of the economic impact of the species, and they are treated equivalently.

It was originally thought that most egg-laying occurred distal to the clusters of grapevines, and so on grape, injury was most important on young vines. Clearly some of the injury we saw was basal to clusters, and those clusters will be lost. While young vines are at particular risk, there is clear economic impact to bearing vines. At this point, it is not recommended to prune out affected shoots, but rather wait until winter pruning.

Fig. 3. Egg nests of periodical cicada may occur either above or below grape clusters.

Coming attractions: The adults of this emergence of Brood X are now a recent memory. As I’ve pointed out in extension presentations, it is wise to avoid planting a new orchard or vineyard a year or two before an anticipated emergence. However, we don’t usually give this warning long enough in advance for sufficient planning, given the lead time needed by nurseries, to get desired scion/rootstock combinations. Here is a listing in order of appearance of broods relevant to Virginia. The most important ones will likely be XIX, II, IX and X. Click on the Brood numbers to see a map.

Brood XIX (13 year): (Southside Virginia) The Great Southern Brood (2024)

Brood XIV: southern OH, KE, TN, MA, MD, NC, PA, northern GA, southwestern VA and WV, parts of NY and NJ (2025)

Brood I: The Blue Ridge Brood: Western VA, WV (2029)

Brood II: East Coast Brood: CT, MD, NC, NJ, NY, PA, DA, VA, DC. (2030)

Brood V: eastern OH, western MD, southwestern PA, northwestern VA, WV, NY (Suffolk Co.) (2033)

Brood IX: southwestern VA, southern WV, western NC (2037)

Brood X: The Great Eastern Brood: NY, NJ, PA, DE, MD, DC, VA, WV, NC, GA, TN, KE, OH, IN, IL, MI (2038)

Addressing a hot topic: Another issue has been broached in the news in the past few days that I would like to comment on. There has been a recent wave of unexplained bird deaths and illness in northern Virginia. Symptoms include blindness or crusty eyes, and neurological problems. The idea was postulated that eating cicadas was responsible for this bird morbidity/mortality. This is circumstantial at best. There were no such problems noted last year in Brood IX in southwest Virginia, nor in earlier emergences of Brood X in northern Virginia.

https://www.ecowatch.com/mystery-disease-killing-birds-2653532689.html

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/28/1011043752/correlation-not-causation-brood-x-cicadas-and-regional-bird-deaths?utm_source%C3%BAcebook&utm_medium%C3%BEws_tab&utm_content%C3%BFgorithm

Cicadas have long been considered a nontoxic food for birds (Leonard 1964, Steward et al. 1988, Williams and Simon 1995). Birds feeding on cicadas have included European starling, common grackles, American robin, wood thrush, blue jay, yellow-billed and black-billed cuckoos, red-winged blackbirds, house sparrow, redheaded woodpecker, tufted titmouse, vireos, terns, laughing gull and ducks. I birded last year with friends in areas of Brood IX adult periodical cicada activity, and we saw no unusual bird behavior (the worst thing was not being able to hear birds above the cicada singing!). Periodical cicadas present an important part of nutrient cycling in forests, and are a nutritional resources for predators (Wheeler et al. 1992).

There is an entomopathogenic fungus, Massospora, that may provide some natural mortality to periodical cicadas. There are compounds in Massospora that are psychoactive in cicadas, causing them to change their behavior (Boyce et al. 2019). One compound in Massospora, cathinone (Boyce et al. 2019), has been known to have psychoactive properties in humans (Langman and Jannetto 2020). But there is no record of eating Massospora-infected cicadas being harmful to birds. Moreover, Massospora is a natural component of the system, and unusual bird maladies are not reported following cicada emergences.

One interview (linked above) speculated whether birds might be picking up insecticides or heavy metals from sprayed cicadas. In an earlier study (Clark 1992), cicadas were not found to be a source of significant levels of organochlorine insecticides or heavy metals for birds. Organochlorines have been replaced by other classes of chemistry, but that group was longer lived, and would bioaccumulate. Modern insecticides should pose less of a hazard in this regard.

So in summary, here are my thoughts on cicada involvement with the bird death/sickness syndrome. If the situation changes, or new information becomes available I’ll let you know:

• There was no issue with bird mortality/morbidity with last year's brood IX, nor northern Virginia Brood X last time.

• Massospora has been a part of the landscape for a long time, with no apparent link to birds.

• There was no apparent bird problem in PA or NJ, nor Tennessee or North Carolina, where Brood X was abundant. Note: Some increasing bird mortality was seen in southern NJ after cicadas had disappeared, well after the outbreak in northern Virginia. This weakens the case for synchrony between cicadas and bird deaths.

• There have been changes in pesticides used over the years, but from last year in Brood IX, there wouldn't be any difference with this year in Brood X.

• If cicadas, fungus, or pesticides are involved, there must be some other environmental change to shift their importance.

Reporting Bird Mortality: The Department of Wildlife Resources has created a reporting form for cases of sick or dead birds:

https://dwr.virginia.gov/wildlife/diseases/bird-mortality-reporting-form/

More later,

Doug

References

Barber, J. E., and A. Nkwanta. 2014. Benjamin Banneker's original handwritten document: Observations and study of the cicada. Journal of Humanistic Mathematics 4: 112-122.

Boyce, G. R., E. Gluck-Thaler, J. C. Slot, J. E. Stajich, W. J. Davis, T. Y. James, J. R. Cooley, D. G. Panaccione, J. Eilenberg, H. H. De Fine Licht, A. M. Macias, M. C. Berger, K. L. Wickert, C. M. Stauder, E. J. Spahr, M. D. Maust, A. M. Metheny, C. Simon, G. Kritsky, K. T. Hodge, R. A. Humberi, GullionT., D. P. G. Short, T. Kijimoto, D. Mozgai, N. Arguedas, and M. T. Kassona. 2019. Psychoactive plant- and mushroom-associated alkaloids from two behavior modifying cicada pathogens. Fungal Ecol. 41: 147-164.

Clark, D. R. 1992. Organochlorines and heavy metals in 17-year cicadas pose no apparent dietary threat to birds. Environ. Monit. Assess. 20: 47–54.

Langman, L. J., and P. J. Jannetto. 2020. Toxicology and the clinical laboratory pp. 917-951. In W. Clarke and M. A. Marzinke (eds.), Contemporary Practice in Clinical Chemistry. 4th Ed. Elsevier.

Leonard, D. E. 1964. Biology and ecology of Magicicada septendecim (L.) (hemiptera: Cicadidae). J. New York Entomol. Soc. 72: 19-23.

Marlatt, C. L. 1907. The periodical cicada. U. S. Dept. Agric. Bur. Entomol. Bull. 71: 1-181. Steward, V. B., K. G. Smith, and F. M. Stephen. 1988. Red-winged blackbird predation on periodical cicadas (Cicadidae Magicicada spp.) - Bird behavior and cicada responses. Oecologia 76: 348-352.

Wheeler, G. L., K. S. Williams, and K. G. Smith. 1992. Role of periodical cicadas (Homoptera: Cicadidae: Magicicada) in forest nutrient cycles. Forest Ecol. Manag. 51: 339-346.

Williams, K. S., and C. Simon. 1995. The ecology, behavior, and evolution of periodical cicadas. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 40: 269-295.

Thursday, May 20, 2021

Brood X of Periodical Cicada Active

Spotted Lanternfly Update

Thursday, February 18, 2021

2021 State Berry School Rescheduled

Friday, February 12, 2021

Southeastern Strawberry School Webinar Series

Wednesday, February 10, 2021

2021 State Berry School

Wednesday, November 4, 2020

Small Fruit News - availability and reader survey

Hello, everyone,

The Southern Region Small Fruit Consortium is a group of stakeholders interested in small fruit production, representing growers, agents and university faculty in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee. The Consortium publishes a quarterly newsletter, the Small Fruit News (https://smallfruits.org/category/small-fruit-news/). Last year, the SFN newsletter was revamped, and a new editorial board established. For the first three issues for 2020, articles were posted as web articles alone. The Fall issue (https://smallfruits.org/category/small-fruit-news/fall-2020/) also contains a link to a PDF version.

We have posted a survey for readers to weigh in on utility of Small Fruit News, and in particular your desire to include a PDF option. Could you please take a few minutes and respond to the survey? The link is included below.

Small Fruit News

Feedback Survey: https://docs.google.com/forms/

You can get find out more about the Small Fruit Consortium at: https://smallfruits.org/

Thanks for your help in keeping the Small Fruit News useful!

Doug P.

Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Management of Spotted-Wing Drosophila in Berry Crops

Details of use of grape root borer mating disruption

Hello, everyone, A question was asked about dates of availability for the Section 18 label for Isomate GRB-Z. I wrote earlier that mating ...